Harv Galic:

Long Sought After, Now Finally Located:

Earliest Substantial Newspaper Description of Yosemite Valley.

Introduction

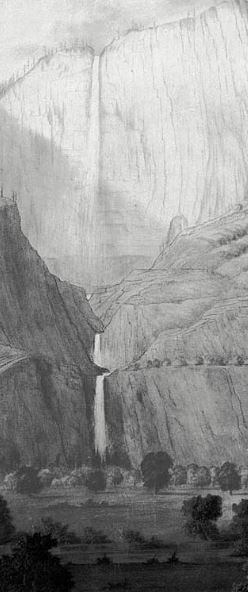

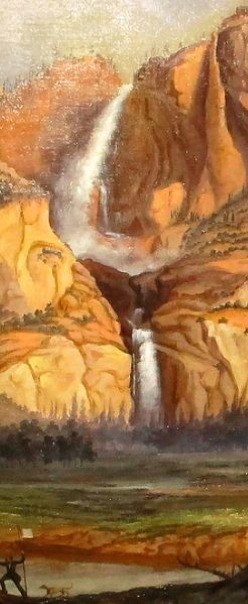

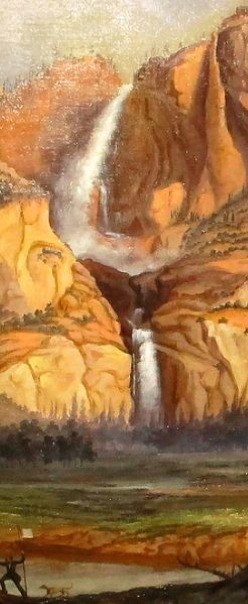

Ayres: The High Falls, 1855

When James Mason Hutchings (1820-1902) set foot in Yosemite Valley in late June 1855, it was the right time for a new phase in the history of that enchanting place. There was no longer need for punitive reprisals against the Ahwahnechee people that were occurring only a few years before, as the Ahwahnechee subtribe had been exterminated by then. The miners no longer cared about access, as it turned out there was no gold anywhere near the Valley. For farmers and herders, the place was still extremely difficult to access and too far from markets where they could sell their crops and livestock. The time has come for writers, painters, photographers, male and female tourist of every degree, adventurers, hotel owners and hotel employees to repopulate the valley. The new, white crowd will now "eat, sleep, gallop, gossip and guzzle" in this former Indian land, which has been taken from them without any recompense.

Some of the men who once took part in the military operations around Yosemite may have thought of taking another look at that wondrous region in the years that followed the Indian Wars, but someone else preceded them: the first to visit the Valley for curiosity and pleasure was Mr. Hutchings in 1855. However, one thing related to Hutchings' first tourist visit has never been fully and satisfactorily resolved: who exactly, or what, really motivated Hutchings to travel to Yosemite?

In 1851 and 1852, when local militia and Army actions against the Indians in Mariposa County reached their peak, newspaper reports focused primarily on skirmishes, with little mention of the terrain and physical features of the Sierra range where these Indian tribes lived. Only a few newspaper articles from that era are known to have mentioned a strange and beautiful mountain valley in passing, but not many details were given. Could one of these early reports have been the inspiration for Hutchings' expedition to Yosemite Valley? This is not very likely. These articles were published in the sections of newspapers that dealt with "Indian troubles", and in their headlines and subtitles there was no mention of a discovery of the wonderful fairy-tale region. Only those readers who were willing to dig deep into the texts would find those paragraphs about Yosemite. But reading newspapers for hours, from the first page to the last, was not part of Hutchings' daily schedule in 1851-52.

Additionally, in the early 1850s he was still preoccupied with his mining exploits, and later zeroing primarily on his bookstore and a letter-sheet printing business. The idea of publishing a California-focused monthly magazine came only later. It is therefore hard to believe that from 1850 to 1852 he would have noticed or paid attention to some of meager and unverifiable claims about California's newest natural wonder, printed in the "wrong" (i.e., Indian war related) section of the paper. In my opinion, if he did get his information from some printed materials, as most 19th century sources (including Hutchings himself) tell us, it must have happened at later time. The best guess would be sometime between early 1853 and late 1854, when the fighting with the Indians had already stopped.

In general, most Yosemite researchers focused on finding an article that mentioned a waterfall about a thousand feet high. Had it been found, such an article would then have been identified as the main motive behind Hutchings' decision to organize his trip. Another, smaller group of scholars had a different goal. They followed Lafayette Bunnell's hint and tried to locate a newspaper article about Yosemite written by U.S. Army officer Tredwell Moore. Bunnell believed that it was Moore's article that first drew Mr. Hutchings' attention to the Valley. Surprisingly, both groups encountered a similar "small" problem: no serious article describing the thousand-foot waterfall, and no newspaper report authored by Lieutenant Moore, were ever found.

In this web document, we revisit the story of that elusive, earliest (pre-Hutchings), non-fictional, newspaper description of Yosemite Valley. A hitherto unnoticed newspaper article, which meets the requirements to a good degree, is presented for the first time. Could this, only recently identified "letter to the editor", published in a small but reputable newspaper and then copied by other newspapers, be the source that brought Hutchings to Yosemite? Maybe it could be. But let's begin this essay by first looking at what Bunnell had to say.

Was J. M. Hutchings the first to describe the Valley in print?

The November 1878 issue of the weekly Mariposa Gazette printed a brief review of Hutchings' latest project:

(Mariposa Gazette, 23 November 1878, p.3, col.2 top):

Mr. Hutchings' Panorama.

————

Mr. J. M. Hutchings, the pioneer of Yo Semite Valley, who was the first to describe it in print, and has for years devoted his time to enlisting the interest of the world in its marvelous and unrivalled cliffs, battlements, waterfalls and scenic beauties, has of late been entertaining the people of Stockton with panoramic views of the Great Yosemite Valley and its surroundings...

The reviewer had no idea that his quite innocent and mostly justified praise of Hutchings would provoke a reaction from a Gazette subscriber from faraway Minnesota. A letter published in the Gazette a few weeks later, vigorously rejected one of the achievements attributed to Hutchings in the above-mentioned review. The author of the letter was Lafayette Houghton Bunnell (1824-1903). He was one of the first whites to enter Yosemite Valley during the conflict between settlers and Indians in Mariposa County in the early 1850s. Bunnell, a native of New York State, resided in California until the end of 1850s, then moved back east of the Rockies. In 1878, Bunnell had just begun to collect material for his book Discovery of the Yosemite, and could not miss such a good opportunity to remind Gazette readers that he, not Hutchings, was the true pioneer of Yosemite and therefore the most reliable and trustworthy source of its recent history. His entire letter to the Gazette, written from Homer, Minnesota {1}, is presented below:

Was Lieutenant Moore the first to describe the Valley in print?

Bunnell's letter was published on December 28, 1878.

(Oops! The day of the week under the logo was

printed as "S

BTURDAY")

(Mariposa Gazette, 28 December 1878, p.3, col.3 bottom, col.4 top):

Letter from Minnesota.

————

Homer, Minnesota, Dec. 16, 1878.

Editor Gazette : – In your issue of the 23d ultimo,

you speak of Mr. J. M. Hutchings

as "the pioneer of Yo Semite Valley, who was the first to

describe it in print", etc. Had this statement appeared in any other journal,

I should have passed it by in silence as I have many errors relating

to the Yo Semite, but as your own paper, under its former name of "The

Mariposa Chronicle", was the first to call public attention to the Yo Semite,

as a matter of history, I think it well to inform you of the fact.

The Mariposa Chronicle was established in 1854, as you are aware, by

Wm. T. Whitachre. Previous to the establishment of his paper, Whitachre

was a "Special" for some of the San Francisco papers. Hearing of the Valley

through Captain Boling and other members of the "Mariposa battalion,"

Whitachre requested me to prepare him an article descriptive of its most

prominent objects of interest, with a view of its being sent to some paper

below. This of course I had not the genius to do, but I promised to give

him some detailed statements concerning the Yo Semite, that probably would

be interesting if dressed in a proper literary garb. With some care I prepared

the promised article. After reading it over Whitachre said in substance:

"Why, Doctor, your estimates of hights are double those of Captain

Boling's, and above all probabilities. If I were to send this down to the Bay

the typos would call it a sell." I was requested to cut down my figures somewhat,

but instead I tore up my manuscript and left Whitachre to obtain

where he could such data as would please him.

Soon after this occurrence the Chronicle was started, but it soon passed into

the hands of Blaisdell and Hopper. Whether under Whitachre's or the

new management, I am now uncertain, but I think some time previous to Mr.

Hutching's first visit to the Yo Semite in 1855, there appeared in the Chronicle

a letter from Lieut. Moore, U.S. A[rmy], descriptive of his expedition of

1852, during which he ordered five of the Yo Semities shot, that had assisted

in the murder of Rose and Shurbon. If you have the old files of the Chronicle,

it will be easy to verify or disprove this statement.

I would not detract from anything due Mr. Hutchings for his energy and

great perseverance in successfully bringing the Yo Semite into public

notice, but if there is any merit due for a first public notice of the Valley,

I think that you will find that it belongs to Lieut. Moore. I am under the

impression that it was Mr. Moore's letter that first attracted the attention

of Mr. Hutchings himself to the Valley. At all events, in his "Scenes of

Wonder and Curiosity in California", he only claims to be "the first in

later years to visit it and called public attention to it." And on another

page while referring to the time of his first visit he says: "Up to this

time we had never heard or known of any other name than Yo Semite", etc.

Very respectfully, yours,

L. H. Bunnell, M. D.

Comments:

Skeptical editor: The name of the incredulous journalist-turned-editor who rejected Bunnell's description of Yosemite was William Thornton Whitacre (1824-1860). (Bunnell misspells the last name as "Whitachre"). Whitacre died in August 1860, so he could neither corroborate nor contradict Bunnell's narrative from the second paragraph in the Gazette. Although Bunnell may have destroyed his copy of that rejected description of Yosemite, we do not know whether Whitacre still kept another copy in his possession "just in case". It would be interesting to know what "prominent objects" and what "estimate of heights" Bunnell used in his text for Whitacre, but unfortunately Bunnell does not specify this. Not too surprising, since his confrontation with Whitacre took place nearly a quarter of a century earlier, so some gaps in his memory were to be expected.

The Lieutenant enters the story: The third and fourth paragraphs suggest that instead of Bunnell's description of Yosemite, Mr. Whitacre allegedly decided to print a "letter to the editor" on the same

theme, Yosemite, written for the Mariposa Chronicle by U.S. Army officer Lieutenant Moore. Tredwell Seymour Moore (1824-1876) was in Yosemite in the summer of 1852. As a commanding officer of a detachment of infantry at Fort Miller on the San Joaquin River, he was directly involved in a bloody battle with Chief Tenaya's Ahwahnechee subtribe in Yosemite. In 1878, when Bunnell presented his answer to the "who did it first" puzzle (see above), Moore was also already dead, and it was no longer possible to obtain his comments or get his confirmation that he had indeed written the letter about Yosemite to the Chronicle. But why would Whitacre seek Moore's help, at a time when Moore was extremely busy with his Army projects and already transferred to another part of California? Wouldn't it have been much easier for him to simply ask one of the locals who traveled with Moore in 1852, or a former militiaman who saw the Valley in 1851, for a description of Yosemite and its wonders? Bunnell did not address this question in the 1878 article (above), but would offer an explanation in his book a few years later.

No takers: The Mariposa Chronicle, which allegedly published Moore's Yosemite letter, did not have a long and happy life. It was launched in 1854, and went out of business after a year and a half. Another newspaper, the Mariposa Gazette, replaced the Chronicle and took over its assets. Bunnell therefore challenged the Gazette editor to check old issues of the Chronicle and find Lieutenant Moore's letter. But despite Bunnell's encouragement that "it will be easy to verify or disprove my statement," editor Angevine Reynolds (1829-1888), apparently did not take the bait. Even if Reynolds took pains to check the archives, he never publicly announced the outcome of this search.

Hutchings' inspiration? In the last paragraph of his 1878 article, Bunnell mentioned his "impression that it was [officer] Moore's letter that first attracted the attention of Mr. Hutchings himself to the Valley". However, Bunnell offered no facts to support this "impression". Therefore, for me, this assumption remains only Bunnell's personal opinion with little credibility.

Bunnell's book

Two years later, in 1880, the first edition of Bunnell's best known book, The Discovery of the Yosemite was published {2}. In the book we learn more about the Whitacre affair. (No luck with spelling of Whitacre's name again; in the book he is called "Witachre" and "Whitachre"):

I complied with [Whitacre's] request as far as I could, by giving him some written details to work upon. On reading the paper over, he advised me to reduce my estimates of heights of cliffs and waterfalls, at least fifty per centum, or my judgment would be a subject of ridicule even to my personal friends. I had estimated [...] the Yosemite Fall at about fifteen hundred feet, and other prominent points of interest in about the same proportion. To convince me of my error of judgment, he stated that he had interviewed Captain Boling and some others, and that none had estimated the highest cliffs above a thousand feet. He further said that he would not like to risk his own reputation as a correspondent, without considerable modification of my statements, etc. Feeling outraged at this imputation, I tore up the manuscript, and left the "newspaper man" to obtain where he could such data for his patrons as would please him.

Bunnell then presented another related story in his book (See p.260 in the Chicago editions of Bunnell's book, and p.263 in the Los Angeles edition). In the early summer of 1851, James D. Savage (1817?–1852), leader of a militia unit called the "Mariposa Battalion," asked Bunnell to visit the U.S. Indian Commissioner, Redick McKee (1800-1886), and convey him that the last outbreak of hostilities between Indians and whites in the central Sierra has now been stamped out. Bunnell and McKee met in Los Angeles in July 1851. During the meeting , it was Colonel McKee who this time showed skepticism when told of the newly discovered marvelous place. McKee first asked for some additional clarifications about that recent flare-up, and then wanted to hear more about Yosemite Valley. The Commissioner at first seemed an interested listener, but it soon became clear that he did not believe in Bunnell's general description of the Valley, much less his estimates of the vertical dimensions of Valley's rim. When Bunnell saw this look of incredulity on McKee's face, he quickly ended the briefing {3},{4}.

In the book, Bunnell repeats his 1878 claim that Moore's letter "descriptive of Yosemite" was published in the Mariposa Chronicle. Moreover, he now seems to be certain that Moore's letter was printed in the very first issue of the Chronicle, on January 20, 1854! He wrote: "I was in possession of a copy of the paper containing Moore's letter for many years, but, finally, to my extreme regret, it was lost or destroyed." Then he continued: "To Lieutenant Moore belongs the credit of being the first to attract the attention of the scientific and literary world, and 'The Press' to the wonders of Yosemite Valley. His position as an officer of the regular army, established reputation for his article..." (See p.278 in the Chicago editions of the book, and p.282 in the Los Angeles edition). On pages 333 / 308 (Chicago / Los Angeles editions), Bunnell concludes that Moore's description "had in 1854 gone out into the world, and [from that time forward] the wonders of the place [became] more generally known and appreciated by the literary and scientific [communities]."

Incidentally, what did not make it into the book was Bunnell's 1878 "impression" that Lieutenant Moore's writing was the main motivation for Hutchings' 1855 trip. Was there perhaps some correspondence between Bunnell and Hutchings in the period 1878-1880, which put that idea to rest? We do not know. However, even to this day there are authors who believe that Hutchings' plans to travel to Yosemite were influenced by Moore's (elusive) newspaper report.

Comments:

Bunnell mistaken? There are several problems with Bunnell's analysis of the events. In 1878, as we saw earlier, Angevine Reynolds, then a newspaper editor in Mariposa, apparently could not locate or even remember any Moore's contributions in old issues of the Mariposa Chronicle. In 1880, when Bunnell was completing his book, the first issue of that newspaper was thought to have been lost or destroyed in the intervening years. Therefore, Bunnell's hypothesis that Moore's article was published in the first issue on January 20, 1854, could not then be directly tested or proven correct or wrong. However, copies of all, including even the first issue of that short-lived publication, have been found since then. Hank Johnston, who had some serious reservations about Bunnell's interpretation of Moore's role, wrote on page 22 of his 1995 book, The Yosemite Grant 1864-1906, that he "recently had the opportunity to examine a virtually complete file of the Mariposa Chronicle, [from] January 20, 1854, to March, 1855,... and [still have] found no letter from Moore...". He then continued, "therefore [it] appears quite possible that Bunnell, writing more than a quarter of a century later, was mistaken about the matter..."

The Lieutenant's false promise: In fact, there is no evidence that Moore wrote any article for any newspaper during his time in California. The occasion when he had perhaps the best opportunity to publish something about his participation in the suppression of the Indian rebellion of 1852 was Moore's visit to the staff of the San Joaquin Republican (Stockton). This was described in the issue of September 4, 1852, p.2, col.4 (top). When asked to comment on Judge Marvin's recent statement about the Lieutenant's expedition to Yosemite and the other side of the Sierra Nevada, Moore said Marvin's report was "substantially correct", but promised to prepare an article for them "with full particulars in relation to [that] affair." But he did not have a chance to keep that promise. About ten days later, without waiting for Moore, the Republican instead published a report by an anonymous member of Moore's expedition, in which those "full particulars" were presented {5}.

Where else was it reprinted? Another fairly convincing argument that Bunnell's story does not hold up is related to his statement that Moore's letter in the Mariposa Chronicle attracted wide attention from scientific and literary circles. However, if such a sensational description of the newly-found valley had really appeared in the Chronicle (or any other paper), it would have been immediately reprinted in other local and national media, as was the custom in those days. But no "clone" of the alleged Moore's original has ever been found. For the sake of comparison, we can mention Hutchings' 1855 "bombshell" description of Yosemite. Even though the issue of the Mariposa Gazette in which Hutchings' report was originally published has been lost, the article itself has been preserved, as it was reprinted in more than 100 local, national and international newspapers.

Busy schedule for Moore: My final argument is that around 1854, when, according to Bunnell, Moore's letter was printed, the supposed author was too busy to spend time communicating with a newspaper editor in a remote mining town in the Sierra foothills. In the spring of 1853, Lieutenant Tredwell Moore was transferred from Mariposa County to Benicia Army barracks. In the summer of that year, he was ordered to explore the mountains of the Coastal Range. From August 6 to September 10, 1853, his group was trying to find the most suitable mountain pass for a railroad route between the San Joaquin and San Jose valleys. He completed his report and submitted it to the Army General Staff on September 17, then took a temporary leave from the Army to participate as chief engineer in a project privately financed by a group of San Francisco investors. The expedition was once again tied to the railway. It was led by John Ebbetts, and the main intention was to find a convenient railroad pass across the Sierra, anywhere between the Carson River in the north and Walker Pass in the south. They left San Francisco on Oct 10, 1853, and did not return until December. Moore then had to prepare a detailed report for the stockholders and complete geographic maps as well as other documentation. This kept him busy during January 1854. That same month, General John E. Wool was named the new commanding officer of the Pacific Department of the Army, replacing General Hitchcock who had resigned. Wool needed two personal assistants and stressed that they must be experts in engineering and surveying. Moore was a good choice and was selected to serve as General Wool's aide-de-camp for the next two years. He continued his active military duty in the West (but not in California) until the outbreak of the Civil War {6}.

If we take into account all that has been said above, the conclusion seems to be quite clear: Bunnell was mistaken, and Tredwell Moore was not the one who first brought the story of the wonders of Yosemite Valley to the general public. The newspaper clipping that Bunnell carried with him for a long time, convinced that it was written by Moore, must actually have been created by a different author.

I really don't want to sound too critical of Bunnell. We should recall that he left California in the late 1850s and became separated from many of his Mariposa friends. He also lost most of his notes from California during the Civil War. After the War he moved to a small isolated hamlet on the Mississippi River in Minnesota. It wasn't until he was in his late sixties that his attention returned to those Indian War days in California. By then, fact and fiction may have already become intertwined in his memory. As a result, some errors, including an exaggeration of Moore's role, found their way into his otherwise valuable book about the discovery and early years in Yosemite.

What did Hutchings say and when did he say it?!

In 1878, Lafayette Bunnell promoted the idea that Hutchings' trip to Yosemite was prompted by a certain newspaper report written by Lieutenant Moore. As we have seen above, a number of arguments can be made against such a proposal. Not surprisingly, a different storyline prevailed among many other early Yosemite chroniclers. According to this alternative scenario, Hutchings' first encounter with Yosemite Valley was closely related to his reading or hearing a tale about a thousand-foot waterfall up in the mountains. One or more unidentified former volunteers in Jim Savage's and John Boling's militia were said to be the source of the rumor.

So let us focus now on Hutchings possible motivation. It is a little strange that we have to speculate as to who or what exactly inspired Hutchings to form a group of 'tourists' and set off with them into that remote valley. Could we not find the answer directly in Hutchings' writings? It turns out that things are not so simple. The story of the connection between Mr. Hutchings and the thousand-foot waterfall first appeared in print around 1867,

but—surprisingly—it was not written by Hutchings himself. Another well known author made the story public first. It took nearly twenty years for Hutchings to finally confirm in print the role of the rumored thousand-foot waterfall. Hutchings verified this only in 1886, in his last major work, In the Heart of the Sierras. Even then, he didn't add a single new piece of information on the subject. Almost everything in the book about the motivation of his first visit has already been told by other authors. What are similarities between these earlier accounts and Hutchings' own explanations, and who first publicized the "thousand-foot" version back in 1867? Here is a closer look:

Thousand-foot waterfall

Professor Whitney (of Mt. Whitney fame) seems to have been the first to publicly state that the source of Hutchings' inspiration for his trip to the Valley in 1855 was a tale of a waterfall "one thousand feet high". In November 1867, Josiah Dwight Whitney (1819–1896) was Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Yosemite Valley Commission. In his Report to the Governor of California, on page 7, he gave a brief outline of the history of the discovery and settlement of the Valley, relying, he said, "on information furnished by persons who have been acquainted with the region since it was first explored by white men." Note that in his Report, Whitney incorrectly stated that whites first entered the Valley in 1852. In fact, this occurred in late March 1851. Whitney then continued: "Some persons connected with Captain Boling's [troop] communicated to the newspapers an account of the wonders of the valley, and especially of the Yosemite Fall, which was described as being more than a thousand feet high." According to Whitney, "this notice, meeting the eye of J. M. Hutchings", eventually resulted in Hutchings' "first regular tourist's visit to the valley in the summer of 1855".

A year later, in 1868, Whitney—now wearing the California State Geologist's hat—published his work The Yosemite Book, in which he corrected, expanded and somewhat altered his earlier account. According to The Yosemite Book, p.19, "some stories told by [Captain John Boling's soldiers] on their return found their way into the newspapers, but it was not until [1855] that any persons visited the Valley for the purpose of examining its wonders, or as regular pleasure travelers [...] One would suppose that accounts of its cliffs and water-falls would have spread at once all over the country. Probably they did circulate about California, [but] were not believed [and were] set down as travelers' stories. Yet these first visitors seem to have been very moderate in their statements, for they spoke of the Yosemite Fall as being more than a thousand feet high, thus cutting it down to less than one-half its real altitude". According to this second version of Whitney's text, "Mr. J. M. Hutchings, having heard of the wonderful Valley, in 1855 [...] collected a party and made the first regular tourists' visit". In 1869, The Yosemite Book became The Yosemite Guide-Book, and went through several more editions over the next five years, but the part describing Hutchings' role in Yosemite early history remained unchanged.

Note that according to Whitney's Report from 1867, Hutchings read ("meeting the eye") the soldiers' reports, while in the 1868 book he stated that Hutchings heard of the Valley. How did Hutchings react to Whitney's two competing proposals? Well, he simply didn't bother to comment. Indeed, there is no mention on how he learned about Yosemite in any of his early writings: nothing on the subject in his California Magazine in the late 1850s, and similarly, not a word in the many editions of his Scenes of Wonder and Curiosity in California, printed from 1860 to 1876.

Those two Whitney accounts were reused by other early writers in the 1870s and 1880s. For example, Bunnell in his book (1880), in the chapters dealing with the history of the discovery and settlement of Yosemite Valley, cites Whitney's Yosemite Guide Book as a source.

Captain Butler's strange story

One author who did not rely on Whitney when describing early visits by whites to Yosemite Valley was the British officer Captain Butler. He stayed briefly in the Valley in the summer of 1873, but it passed another five years before his description of that trip was published. His little-known account first appeared in a weekly magazine printed in London, 1878 {7}. His story begins with a short, curious, and thoroughly "sanitized" version of the Yosemite history. Despite the fact that his introduction is, so to speak, very imaginatively written and with little connection to actual events, some parts of his narrative are relevant to the topic of this essay. A condensed version of his introduction is presented in the next few paragraphs. Unlike that introductory segment, the rest of Butler's text is a well-written and balanced description of the Valley and the surrounding peaks and waterfalls.

According to Butler, a group of Indians from the Yosemite tribe one day swept bunch of cattle from ranches in the Sierra foothills. The owners immediately organized a search for these animals. The pursuers followed the Indian tracks and eventually reached an unknown valley. They are surprised by its beauty. Their cows were found grazing in valley's lush meadows. The Indians wisely chose to hide, and the ranchers recaptured their well-fed animals and brought them back home. The Indians and the settlers lived together happily ever after. [Yeah, right!]

Butler's version of history does not mention the fighting, the bloodshed, or the extermination, presumably to make his text more palatable to British readers who may not have wanted to hear anything about anti-Indian violence in the U.S. What is even more bizarre about Butler's text is the way he introduces Hutchings into the story. According to Butler, those who saw the valley couldn't wait to tell their friends about the marvelous region they had visited. The highest waterfall in the valley was the main topic of their conversations. One of the explorers said: "It falls one thousand feet!" But the neighbors shook their heads. "One thousand feet! Impossible!" What follows is a direct quote from Butler's text [emphases mine] {8}:

There was a farmer listening to the story who thought to himself deeply over the marvels of the place. "A waterfall," said he "one thousand feet from top to bottom! Niagara is but one hundred and sixty feet, and yet tens of thousands of visitors flock to it.

I will go to the foot of the fall that is one thousand feet high [...], build there a hotel and make a fortune. He was true to his word. Opposite the great fall of the Yosemite this farmer set his stakes. [...] To-day, out of all the [hotels] in the wonderful valley, that of Farmer Hutchings holds its own.

Marvelous! How did Butler come up with this story?! Was it based on his conversations with some residents of the Valley in June 1873, when he was there? Did he talk to Hutchings? If he did, wouldn't he know better than to call him "farmer"? Or has Butler, just as in his description of the settlers and the Indians, taken the liberty of adding a romantic touch to his introduction and making Hutchings "one of them" farmers? In any case, in Butler's version it was word of mouth, not a newspaper report that stimulated Hutchings' curiosity. And what about the height of the falls and the "thousand feet" figure he used? Was that borrowed from Whitney, or perhaps from another (now forgotten) early author? These are just rhetorical questions at this point. We'll find another surprise when we compare Butler's and Hutchings' "Niagara vs. Yosemite Falls" segments.

Niagara

In his book In the Heart of the Sierras (1886), Chapter VII ("The First Tourist Visitors to Yo Semite"), Hutchings wrote for the first time about his motives and circumstances of his initial visit to Yosemite in 1855 (see pages 79-80). He tells that upon the return of the Mariposa Battalion to the settlements [in 1851], "little seems to have been said, and that little very casually, about the marvelous grandeur of the Yo Semite, [and] but little found its way [...] to the public through the press of that day". However, one of those reports caught his attention. What follows is a direct quote from Hutchings' book [emphases mine]:

As the account given, however, mentioned the existence of "a water-fall nearly a thousand feet high", it was sufficient to suggest a series of ruminating queries. A water-fall a thousand feet in height, and that is in California? A thousand feet? Why, Niagara is only one hundred and sixty-four feet high!

A thousand feet!! The scrap containing this startling and valuable statement, meager though it was, was carefully treasured, [and] about the twentieth of June, 1855, the water-fall a thousand feet high induced the writer [i.e., Hutchings] to form a party to visit [the place].

Isn't it amazing that Hutchings' description, written around 1886, bears so many similarities to Butler's segment, written between 1873 and 1878? A strange coincidence? And how is it that Whitney, not Hutchings, was the first writer to connect the tale of the thousand-foot waterfall with Hutchings' Yosemite tourist expedition? Fortunately, these puzzles can be easily solved. Everything falls into place if we note above the frequent use of the idioms "in writing" or "in print". It is true that Whitney was the first to mention the thousand-foot waterfall in print. Similarly, Butler was one of the first authors to compare Yosemite and Niagara Falls in writing. But the real source for both—I firmly believe—was none other than James Hutchings!

True, Whitney and Butler were the first to publicize these catchphrases and one-liners about Yosemite Falls and Niagara through printed media, but almost certainly it was Hutchings who invented, used and propagated them years earlier in his conversations and lectures. When Hutchings and his family relocated to Yosemite in the spring of 1864, they ran a hostel there. Hutchings focused primarily on culinary perfection and shared social experiences, not so much on improvements to his guests' living quarters. To compensate for the lack of top-of-the-line accommodation

{9}, Hutchings surrounded the patrons with "loving hospitality" (to quote Helen Hunt Jackson) and an enthusiastic welcome. In the evenings, Hutchings often regaled his guests with stories of Yosemite during special "campfire lectures" on a small clearing by his "hotel" {10}. There were no printed versions of these "lectures", but attentive visitors and guests, like Captain Butler, may have taken notes, which might eventually end up in newspaper accounts of their trips to Yosemite. On the other hand, Whitney didn't even have to rely on bonfire events. As a powerful member of the Yosemite Commission, he certainly could have had access to Hutchings whenever he needed it, for example, in the fall of 1867, while he was preparing his first report on the history of the discovery and settlement of the Valley. Hutchings soon discovered another way to spread his Yosemite stories without printing them. In the 1870s and 1880s, mostly during the winter tourist hiatus, he traveled the country and gave hundreds of well-received talks and lectures about Yosemite. No doubt one of the questions he would often be asked would be about the motivation that brought him to Yosemite in 1855. He must have enjoyed pointing out to listeners that the rumored "thousand-foot cascade" turned out to be the largest leaping waterfall in the world, with a stunning vertical distance from top to bottom of 2,565 feet.

Comments:

Scrapbook:

Hutchings wrote in his book that one particular account about Yosemite had caught his attention and that the "scrap containing this startling and valuable statement... was carefully treasured". However, it is not entirely clear whether his "scrap" was a newspaper article, or was he referring to something he heard from eyewitness in the mining camps, while the "scrap" was his handwritten note about that anecdotal startling waterfall. Hutchings' scrapbook is kept at the Yosemite Museum, but I don't know if it contains notes or newspaper clippings that would clarify this matter. It is also possible that Hutchings lost this very important piece of information somewhere along the way, just as Bunnell did with his treasured "Moore's" article.

Another version:

We have seen that Whitney published two slightly different versions about Hutchings' role in opening the Valley to the world. Similarly, Hutchings produced at least one additional version, slightly different from that presented in his 1886 book. In the Souvenir of California. Yo Semite Valley and the Big Trees of California, an affordable and popular guide to the Yosemite region, first printed in 1894, Hutchings wrote:

Strange as it may seem, upon the return of the soldiers from [pursuit of Yo Semite Indians], no mention whatsoever was made of the unspeakable grandeur of Yo Semite. Incidental allusion, however, was made to a waterfall, they "guessed, was a thousand feet high!" The sight of this scrap started a number of ruminating queries in the mind of the writer, who was then gathering materials for an illustrated monthly..., and he resolved to obtain a sketch of this "waterfall one thousand feet high."

Again, it is not clear whether the "incidental allusion" in the paragraph above was related to a newspaper article or to something Hutchings merely heard from the soldiers.

So far we have covered a lot (or maybe too much) of background material. The time has finally come to present the newly discovered newspaper report from the pre-1855 period that contains a fairly realistic description of Yosemite Valley.

Here comes Caminante

On November 22, 1853, an anonymous contributor "from Buckeye Gulch", near Mariposa, sent a letter to the editor of Stockton's leading newspaper, the San Joaquin Republican. This was his first letter to that paper. Two more will follow, making a total of only three contributions that can be attributed to that anonymous author. The writer introduced himself as someone who was not personally known to the editor, although he was bound by "long standing friendship and pride of acquaintance" with that "meritorious paper". He then began his report with a brief description of the changes caused by "wintry anticipations" in the lives of merchants, miners and others in his neighborhood. In his report, he also mentioned several weather-related deities from Roman mythology by name, thereby telling readers that he was probably a person holding some higher degree of education. His letter was published on the first page, (col.1), of the Republican on Novembers 29, 1853, and was signed by his nom de plume, Caminante. This Spanish word could be translated as hiker, walker, wayfarer, or, e.g., mountaineer. Although the editor of the Republican, George Kerr, may have eventually found out who was hiding behind this pen name, he never got around to publishing it: as fate would have it, Mr. Kerr died a few months later. Strangely, the place from which the letter was sent, Buckeye Gulch near Mariposa, was never mentioned in any other article or book from that era. It is true that today a small seasonal stream south of Mariposa and near Mormon Bar is called Buckeye Creek. There is also evidence of some mining activity near that creek in the 1850s. Perhaps Buckeye Gulch was an unofficial name of a short-lived and long-forgotten cluster of houses and mining cabins conveniently located near the creek? More research would be needed to confirm this assumption.

The next time we heard from Caminante, it was a stunner! This was his second letter to the Republican. He begins by stating that in California, already noted for its extraordinary mineral production, still more interesting features of a surpassing character are to be found. "Chief among the latter", says the author, "is in this County, about 40 miles north-east from the town of Mariposa". Of course, he was talking about Yosemite Valley. Caminante's letter to the editor consisted of two parts. The first part was a description of the Valley. The second part talked about former inhabitants of the Valley, a "savage and mischievous" Indian tribe, supposedly the source of all kinds of troubles for white miners and settlers. I am presenting the contents of the letter in two separate segments, but please note that there is only one undivided article in the newspaper, not two. Caminante wrote his letter in Buckeye Gulch on December 5, 1853. It was published in the San Joaquin Republican a week later, on December 13, 1853, on the front page, in the first column.

There was but one more letter by Caminante to the Republican, this time regarding some political issues close to his heart. This, his last contribution, undated but also from Buckeye Gulch, was published on February 23, 1854, on page 2, col.4.

And then Caminante disappeared forever!

Year 1853: First realistic description of Yosemite Valley

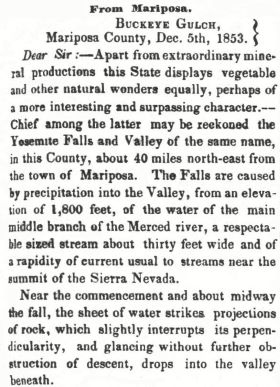

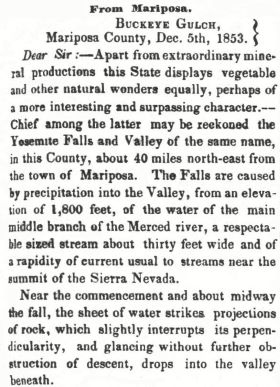

(San Joaquin Republican, Stockton, 13 December 1853, p.1, col.1):

From Mariposa.

Buckeye Gulch,

Mariposa County, Dec. 5th, 1853.

Caminante's article

(opening paragraphs).

— Apart from extraordinary mineral

productions this State displays vegetable

and other natural wonders equally, perhaps of

a more interesting and surpassing character.—

Chief among the latter may be reckoned the

Yosemite Falls and Valley of the same name,

in this County, about 40 miles north-east from

the town of Mariposa. The Falls are caused

by precipitation into the Valley, from an

elevation of

1,800 feet, of the water of the main

middle branch of the Merced river, a respectable

sized stream about thirty feet wide and of

a rapidity of current usual to streams near the

summit of the Sierra Nevada.

Near the commencement and about midway

the fall, the sheet of water strikes projections

of rock, which slightly interrupts its

perpendicularity, and glancing without further

obstruction of descent, drops into the valley beneath.

The length of the Valley is 12 miles, with

a varying average breadth from 3/4 to 1 mile.

It follows the course of a large confluent of

the Middle Fork, which mouths a short distance

below the cataract and meanders its

almost entire length. Enclosed on every side

by stupendous, abrupt, perpendicular mountain

walls, it sits a gem of fertility, deeply embosomed

in the rugged still seclusion of the

Sierra Nevada. Although for a greater portion

of the year surrounded by cliffs and peaks

of snow, it is nearly altogether exempt from

such a visitation, except when its surface is

occasionally whitened by a snowy roof, which,

lingering a moment disappears forever before

the influence of a uniformly mild and agreeable

atmosphere. When the snow is melting

in the spring and summer, numerous ravines

from the summit and face of the adjacent dizzy

over-hanging cliffs, form a thousand fancifully

varying leaping and dashing cascades, whose

infilt[r]ating particles aid in fertilizing the

almost smooth surface of the valley with a luxuriant

and perrennial verdure. Passing up

the valley through occasional clefts and depressions,

the traveler obtains glimpses of

scenery, which for wildness and grandeur are

singularly startling and wonderful.

Nature seems here to have disguised a conjoint

expression of the extremes of the bland[,]

the beautiful and seductive, with the wild, the

grand, the awful and forbidding—to which

not inharmoniously, blends the din and roar of

the waterfall—at familiar distance falling upon

the ear as incessant thunder and with stupifying

effect.

(the text of the article continues below)

How does this compare to earlier newspaper descriptions?

Before moving on to the second part of Caminante's article, let us first compare the above description with two previous attempts to present Yosemite Valley in print. The earliest newspaper depiction of the Valley that I know of is from April 1851. It was published in the San Francisco newspaper, Daily Alta California, on April 23, 1851, p.2, col.2. The article was written by John Gage Marvin (1815-1857), (a.k.a. "Judge Marvin"). His article describes actions against Yosemite Indians and other nearby tribes by the local militia under Savage's command. Only two sentences in the middle of the article are devoted to the physical characteristics of the Valley {11}.

The rancheria of the Yo-Semitees is described as being in a valley of surpassing beauty, about 10 miles in length and one mile broad. Upon either side are high perpendicular rocks, and at each end through which the [Merced] Middle Fork runs, deep cañons, the only accessible entrances to the Valley.

Not a word about waterfalls and no estimates of how high the "high perpendicular rocks" are.

The following year, in September 1852, a civilian accompanying the U.S. Army troops under Lieutenant Moore through Yosemite and all the way to Mono Lake, gave a few more details about the Valley in his text {5}. The author was bold enough to even include an estimate of the height of the cliffs surrounding the 'magnificent' place. He was also impressed by the beautiful 'cascades' on both sides of the valley rim {12}. For us, the relevant part of his narrative is in the last paragraph:

The valley of Yo-semite varies from about one fourth of a mile to one mile in width, and about twelve miles in length; the sides are perpendicular cliffs, and from about 400 to 1600 feet high; the scenery is most magnificent, for nothing can exceed the beauty of the cascades on each side of the valley—about six in number. The soil is too wet for either grazing or agriculture, as the valley is overflowed the greater part of the year, and there is no appearance of gold in the valley as far as I could discover.

Comment:

In fact, in the time gap between the appearance of those two descriptions of the Valley, another author tried to do the same. However, the features of the Valley and the estimation of its dimensions are so far from reality that I don't consider this attempt seriously, and I mention it only for the sake of completeness. The San Joaquin Republican of June 16, 1852, published that article under the title "Another Indian War". The editor identified the author only as "a friend". The main focus of the report was on the "Yeosemoty" tribe. The author wrote:

They inhabit a beautiful and fertile valley in the upper Sierra Nevada, on the middle fork of the Merced, known as Yeosemoty Valley. This valley is about sixty miles in length, with an average of three in breadth, the surrounding peaks are covered with perpetual snow, and it is known that there is gold in the vicinity.

Note that the main interest of the writers (and readers) in those days was the military aspect of the events, while the natural wonders of the area were more of an afterthought. On the other hand, Caminante's text has different priorities. His focus seems to be on making California readers aware of an incredible and unique scenic attraction, hidden—so to speak—in their backyards.

Now let us look at the remaining content of the Yosemite article. My impression is that this second segment came from one or more different sources, not the source that the writer used for the first part of his text {13}. The Indians who once inhabited Yosemite were characterized as "savage and mischievous", ready to cause trouble for white miners and settlers who relentlessly encroached on their territory. Caminante's source does not hesitate to use false rumors or only partially true stories to justify later punitive actions by whites against the Yosemite Indians.

(continuation from above)

The Yosemite valley and region contiguous,

are possessed by a tribe of Indians bearing the

[same?] name. They are savage and mischievous, as

many resident in and near the Mariposa, Agua

Frio, Bear Valley, and Shirlock's settlements

can bear testimony, by irritating experience of

recent systematic loss and destruction of property,

and sometimes of life by the incautious

and venturous. Of all the various tribes of

this region, this alone evince an obduracy and

deafness to the voice of civilization. Two

years ago, being urged upon this subject, their

Chief expressed his own and the sense and resolution

of the tribe, with the curt, contemptuous

remark, "that he could neither be bribed

by the white man's baubles nor bought with a

red shirt".

Caminante's article

(closing paragraph).

In 1851, the Falls and Valley

were visited and partially explored by a military

party in pursuit of Indians ; since when,

few have ventured there. Some months later,

a party of Frenchmen, on a prospecting tour,

were all massacred, except one, who escaped

his companions fate by concealment in the cloud

of spray between the rock and the impact of the

waterfall.

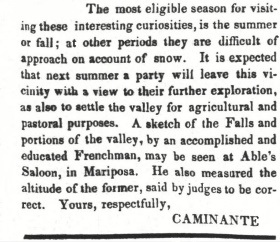

The most eligible season for visiting

these interesting curiosities, is the summer

or fall; at other periods they are difficult of

approach on account of snow. It is expected

that next summer a party will leave this vicinity

with a view to their further exploration,

as also to settle the valley for agricultural and

pastoral purposes. A sketch of the Falls and

portions of the valley by an accomplished and

educated Frenchman, may be seen at Able's

Saloon, in Mariposa. He also measured the

altitude of the former, said by judges to be correct.

Yours, respectfully,

Caminante.

Comments:

Chief Tenaya:

Little is known about Chief Tenaya, one of the leaders of the Ahwahnechee people in the turbulent early 1850s. From a white perspective, the best source is Bunnell, who was one of the few Anglo-Americans who had the opportunity to meet and interact with Tenaya (albeit through a translator). Bunnell collected some of the chief's utterances in his book. Two other people who spoke with Tenaya were Major Savage and Captain John Boling. (Boling would later become Mariposa County Sheriff). We can also find a few words about Tenaya in Hutchings' texts. This particular statement of Tenaya, quoted by Caminante, "I could neither be bribed by the white man's baubles nor bought with a red shirt", was previously unknown. It sounds pretty authentic, and Caminante probably got it from an eyewitness. Since Savage was already dead in 1853, the most likely sources for this statement could have been Boling or Bunnell. The "red shirt", which Tenaya mentioned, was probably a reference to the red garments worn by Savage's volunteers and the Major himself {14}.

Frenchmen massacred:

The story of the "massacre of a group of Frenchmen" did indeed circulate among the miners in the area, but was largely fabricated, probably to incite them to violent revenge. If Caminante had taken time to learn more about the chronology of the event, he would have learned that there was no "massacre" and probably would not have mentioned this fictional episode. What is known is that eight prospectors, originating from several different countries, entered the Valley at the end of May 1852, despite warnings not to go there. Two miners were killed under suspicious circumstances by local Indians who may have been provoked. What followed was the Army's bloody vengeance against the tribe. Hank Johnston compiled all the known material about this event in his detailed and well written article, "The Mystery Buried in Bridalveil Meadow", published in the journal Yosemite, Volume 54, Number 2, in the spring of 1992.

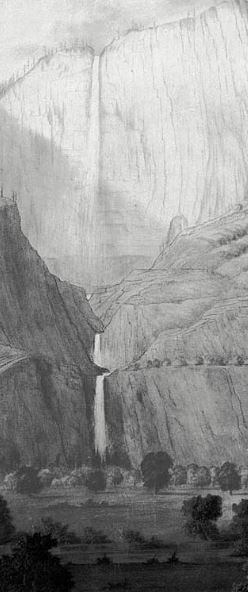

Claveau: Yosemite Falls, 1858.

Did he make an earlier sketch in 1853?

Year 1853: First sketch of Yosemite Falls?!

Are we in for another shocker? It is generally accepted that the first artist to visit Yosemite Valley was Thomas Ayres, who accompanied a group led by Hutchings in 1855. Similarly, Ayres is credited with the first drawing of Yosemite Falls. But Caminante now suggests that in 1853, or even earlier, a French artist sketched, and later exhibited at Mariposa, a drawing of Yosemite Falls and "portions of the valley"! We don't know who this "accomplished" Frenchman was, nor is it clear whether his sketch was based on the artist's personal experience. That artwork, e.g., could also have been the result of a partnership between a person who actually saw the waterfall and a painter who carefully interviewed that eyewitness afterward. We do know that in 1856/57, French painter Antoine Claveau (born about 1815, died perhaps mid/late 1870s) worked in Mariposa and Yosemite while preparing the "panorama" of the Valley for the Mann brothers. Claveau arrived to San Francisco from Chile on September 28, 1849, so—in theory—he could be the mysterious Frenchman. But, of course, the unidentified author easily could have been someone else. For example, Hutchings is known to have traveled in 1854 with another French artist, Edward Jump. Unfortunately, at the moment, nothing can be reliably said about who the "educated Frenchman" was. Let us note that, according to estimates, about thirty thousand citizens of France arrived in the California goldfields, and there is no doubt that at least some of these people were budding painters. Finally, was there an "Able's Saloon" in Mariposa, where—according to Caminante—a drawing of Yosemite Falls was exhibited in 1853? Yes, I can confirm that in 1853 and later, one Green B. Abel (note the slightly different spelling) was proprietor of the "Billiard Saloon" on Charles Street, between 3rd and 4th Streets in Mariposa {15}.

How widely was Caminante's article distributed?

Caminante's article was fairly well received. It should be recalled that it was published not long after the discovery of the Calaveras Big Trees groves. Thus, news about the supposed giant waterfall in Yosemite had to compete for space and credibility with articles about "mammoth trees" and other natural curiosities of California. Caminante's article on Yosemite Falls was originally published on December 13, 1853, in the San Joaquin Republican. At that time, the Republican was widely read in the southern parts of the Central Valley as well as in the mining communities of the central and southern Sierra. The article soon attracted the attention of other newspaper editors, not only in California but even on the East Coast.

Three days after its original publication, on December 16, 1853, the article was reprinted in the Sacramento paper Daily Democratic State Journal, under the headline "Yosemite Falls and Valley". The author of the original text was identified only as a "correspondent [of] the Stockton Republican", but neither the pseudonym "Caminante" nor Buckeye Gulch were mentioned. The version in the Sacramento paper is a complete copy of what I call the "first segment" of the original article, but the part about the Indians and the advice about when is best time to visit the Valley have not been reprinted. Although the Democratic State Journal was not the most popular paper in Sacramento, it nevertheless reached a significant readership in the northern parts of the Central Valley and in the northern mining districts.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1853, Caminante's report was reprinted in the Daily California Chronicle, a San Francisco newspaper. The editor added a few introductory sentences, but the rest was the complete and unaltered original text from the Republican, including the section on Indians. It was the only newspaper other than the Republican to identify the original author as "Caminante" rather than "a correspondent". As with Sacramento's Daily Democratic State Journal (above), the Daily California Chronicle was not the largest circulation paper in San Francisco at the time, but it still had a solid subscriber base in the city and surrounding areas. The title of the article in the Daily Democratic was set to "Yosemite Falls—1800 Feet High." Here is a short introductory paragraph added by the editor. (Note also an early comparison with Niagara Falls):

Yosemite Falls—1800 Feet High.— A correspondent of the

San Joaquin Republican, writing from Mariposa county,

gives the following account of a great natural wonder

in that county. The sublimity of the Yosemite Falls can be

estimated, in a measure, by comparing their height with that of

Niagara; the former being 1800 feet, and the latter only 160 feet.

The body of water however, which flows over the precipice at

Niagara is much greater, being a stream three-quarters of a mile

wide, forty feet deep, and flowing with a current of seven

miles an hour. [End of Intro].

On the last day of that year, December 31, 1853, the editor of Auburn's Weekly Placer Herald used Caminante's original article, or perhaps one of the above 'clones', to compose a short 'filler' for his paper:

Yosemite Falls.— These falls, which

are on the main middle fork of the Merced river, in Mariposa county,

are 1800 feet high.

Similarly, the Democratic State Journal, Sacramento, January 2, 1854, added a few sentences about the Falls. This was the second mention, though—this time somewhat confusing—of Yosemite Falls in that newspaper in a two-week period:

Highest Falls in the World.— The Yosemite Falls in[!]

the Merced river, in Mariposa county, are said to be 1,800 feet high. If such is the

fact, the falls must be high up in the mountains where the stream is small[?!].

The Sacramento Daily Union was one of the largest-circulation California newspapers of the era. Its editor also decided to reduce the original article to just a simple 'filler' that was printed on January 5, 1854:

Yosemite Falls. — These falls, on the main middle fork of the Merced river, in Mariposa county, are said to be 1,800 feet high.

The next day, January 6, 1854, a short segment about Yosemite was printed in the The Pacific, a San Francisco weekly:

Yosemite Valley lies 40 miles north-east of Mariposa, some twelve miles long and about one mile wide, and enclosed by high, precipitous mountain walls, over which tumbles the main branch of the Merced river, some 1800 feet in descent, as stated by a correspondent of the San Joaquin Republican.

I was quite surprised that Caminante's article was also reprinted in three Connecticut newspapers. It first appeared in the Hartford Daily Courant, February 6, 1854. The original Republican article was slightly edited and shortened, and the Courant editor also took the liberty of adding some of his own biases to the paragraph on Indians, see below. This February 6 version was then reprinted in a weekly journal called The Connecticut Courant on February 11, 1854, and in the Norwich Courier, Norwich, CT, on May 3, 1854. Here is the altered passage about the Yosemite (Ahwahnechee) Indians [emphasis mine]:

The Yosemite Indians inhabit this region of country. These are one of the most savage and cruel tribes of the West. In 1851 a party of Frenchmen visited this spot on a prospecting tour. While passing through the valley they were suddenly attacked by a band of the Indians, and all were massacred save one, who escaped the fate of his companions by concealing himself in the cloud of spray be[t]ween the sheet of the descending waterfall and the rock. Since then, few have ventured to explore the spot...

The last paragraph of the original article was skipped in the Connecticut versions, and Caminante was not mentioned. The event that later became known as the "Massacre of French miners" should have been set in 1852, not 1851.

It is entirely possible that some other 'clones' of Caminante's Yosemite article were published in and out of California between December 1853 and April/May 1854. If you know of any such finds, not already mentioned above, please let me know.

What is known about Caminante?

We know only a few facts about this Republican's correspondent from Mariposa County. He seems to have been a newcomer to the area. We know that he lived in Buckeye Gulch, a few miles southwest of Mariposa and near Mormon Bar, from at least November 22, 1853 (his first letter to the Republican) to 23 February 1854 (his third and last correspondence). After February 1854, the Republican began to rely heavily on a new local paper, the Mariposa Chronicle, as a source of news and commentaries from Mariposa, and thus no longer needed a personal correspondent. It is also possible that Caminante simply left Mariposa County after February 1854, and consequently ended his newspaper's journalistic career in this part of California.

Caminante clearly had more than a basic education, or so he wanted us to think. As to his political affiliation, it is not clear whether he was a Democrat or a Whig. In his last article for the Republican, (not featured in this essay), he strongly opposes attempts by Democrats to fill California's vacant U.S. Senate seat by voting in the California Legislature (where Democrats then held a majority), rather than waiting for a general election in which citizens would determined the outcome with their vote.

I am convinced that Caminante was not an eyewitness to any of the events that led to (re)discovery of Yosemite. It is much more likely that he simply compiled information he received from several active participants in the 1851/52 events in the Valley, including perhaps even from Bunnell. Although Bunnell may have torn up the original of his note to Whitacre on Yosemite, another copy, in Whitacre's possession, may still have existed, and Caminante could have used it for the first part of his article.

An interesting possibility

There is a certain non-zero possibility that the person operating under the alias "Caminante" was none other than Bunnell's nemesis, William T. Whitacre, co-editor-designate of the Mariposa Chronicle. It is known that in late 1853 Whitacre and his partner Alfred Gould were preparing to start a new weekly called the Mariposa Chronicle. An announcement was sent to other California newspapers that the first issue of the Chronicle would be published on January 2, 1854 in Mariposa. Whitacre and Gould must have begun frantically gathering material for their first issue. This may have been why Whitacre interviewed Bunnell and several other locals about the rumored newfound spectacular natural wonder at the headwaters of the Merced River.

But then something happened in December 1853, and it seemed as if Whitacre had become disillusioned and convinced that the whole project was doomed to failure. Perhaps a problem with funding, or perhaps a disagreement between Whitacre and Gould over the political orientation of the new paper. What is known for certain is that in early December several newspapers, including Stockton's Republican, ran a note that the planned launch of the Chronicle had been cancelled. This prompted Gould to send a correction to the Stockton paper, stating that the launch had not been abandoned, but merely delayed, on account of Mr. Whitacre's "sudden and somewhat protracted illness", and that "the paper will be out, certainly before January 13th."

This is where speculation begins to creep into our story. Whitacre may not have been as optimistic as his partner Gould. He might have concluded that it was time to offload some of the most interesting material he had collected for the 'doomed'

Chronicle, such as the Yosemite article, to some other newspaper. One consequence may have been that the publication of the earliest realistic description of Yosemite ended up in Stockton, rather than Mariposa, as originally intended.

We know that the revised launch date of January 13th also came and went without the new Mariposa paper appearing. But seven days later, after the partners may have temporarily reconciled, or the funding issues temporarily resolved, the

Mariposa Chronicle finally saw the light of day. Note that Whitacre-Gould partnership didn't last long. It was dissolved "by mutual consent" on Apr 18, 1854, when Whitacre bought out Gould. Whitacre himself didn't stay in Mariposa much longer. He sold the newspaper to Blaisdell and Hopper in July 1854, and left the area forever (just like "Caminante" did!)

Back to Bunnell. Was the article in his possession the one written by Caminante?

If Bunnell kept a newspaper clipping with a realistic description of Yosemite Valley "for many years", it was almost certainly a compilation of our anonymous journalist "Caminante". Bunnell may have clipped his original text from the Stockton Republican or owned a Sacramento or San Francisco reprint. Recall that the San Francisco newspaper (Daily California Chronicle) credited "Caminante" of "Buckeye Gulch" with authorship, while the Sacramento Daily Democratic attributed authorship to an unnamed correspondent with no address. Bunnell's adamant belief that the article in his scrapbook was written by Lieutenant Moore suggests that his clipping was likely the unsigned version from the Sacramento paper. If, on the other hand, Bunnell possessed the version with Caminante's signature, he would first have to explain to himself why Moore would use that strange pseudonym, as well as why he would give an address in Buckeye Gulch, when in fact his official address was Fort Miller or the Army barracks in Benicia.

Back to Hutchings. Was Caminante's article his spark of inspiration?

The title of this subsection raises a question that is almost impossible to answer with certainty. The only development that would provide a 100% guarantee would be locating a clipping of Caminante's article somewhere among Hutchings' papers stored at the Yosemite Museum. However, we can play with probabilities and percentages, and perhaps at least estimate the most reasonable answer. First, it is almost certain that Hutchings' famous "thousand-foot waterfall", was never mentioned or even hinted at in any California newspaper or book printed in the period 1850-1855. Otherwise it would have already been found.

The absence of such a printed source still leaves open the possibility that Hutchings learned of the falls through conversations with some of the participants in the militia/military punitive raids in Yosemite Valley in the early 1850s. We can imagine Hutchings sitting outside a ramshackle cabin, in the gleam of moonlight, talking to an ex-combatant now back in a mining camp. The man recounted a story of a beautiful valley far up in the mountains, and claimed to have seen an astonishingly tall waterfall there, perhaps even a thousand feet high. How would Hutchings react? He was an ambitious man who may have loved adventure and excitement, but who was certainly not foolish. Would he really immediately decide to organize a large, expensive and risky expedition into the unknown, just on the basis of some meager, unconfirmed tale of a lowly miner? Probably not! But he probably wouldn't even completely reject such rumors. At some later time, and at just the right moment, Caminante's well documented account appeared in a reputable newspaper. Wouldn't that provide the necessary spark of inspiration and allow Hutchings' imagination to fire? With this added incentive, his earlier musing about a trip to Yosemite would now crystallize and soon become a reality.

Well, there is one small problem with this scenario. Wouldn't Caminante's estimate of the height of the falls (remember, he quoted "1,800 feet") be reflected in Hutchings' evening stories to his hotel guests, in his lectures around the country, and eventually in his most famous book? But as it was, he stuck to the figure of one thousand, and not to one thousand eight hundred. Isn't that good enough evidence that Hutchings never saw Caminante's compilation? Not necessarily! One explanation would go like this: Hutchings was a gifted storyteller, and he could have easily realized that comparing the true height of the falls with the height he had previously heard from the miners ("one thousand feet"), would elicit a much stronger reaction from the audience than comparing the actual height to Caminante's "1,800 feet". So this was not about deceiving the listeners, but a matter of choice. He could have simply decided to use the "first-in first-out" strategy.

To recapitulate:

This document aimed to answer two related questions. First, was there any realistic description of Yosemite Valley in print prior to Hutchings' acclaimed Mariposa Gazette article of August 1855? The second question was: How did Hutchings find out about Yosemite and what motivated him to go there? We saw in the opening sections of this essay that Bunnell's answer to both of these questions was:

All the credit must go to Lieutenant Moore!

But the further and deeper we investigated Bunnell's proposal, the clearer it became that Tredwell Moore had never printed any description of the Valley. Some other early Yosemite explorers linked Hutchings' motivation for traveling to Yosemite to a newspaper report that mentioned a thousand-foot waterfall. But just as Moore's description has never been found, similarly—to this day—no one has been able to locate anything published between 1851 and 1855 that suggests a height of Yosemite Falls of (more or less) a thousand feet.

With the chances of the "thousand feet" article ever being found dwindling, an alternative approach gained traction: Hutchings might not have read about it, but he might still have heard about the Falls while talking to former soldiers or militiamen. This is certainly a possibility, but I would argue that meager and unconfirmed rumors alone would not be quite enough to spur Hutchings to action. However, had he later seen a more detailed Yosemite description in print, that could have been the pivotal moment in his decision-making.

An article that fulfills just such a role was found recently. In this work it is presented to the public for the first time. The article appears to be a compilation by an anonymous writer calling himself "Caminante", and it was published in the San Joaquin's Republican of Stockton on December 13, 1853. If Hutchings saw Caminante's account and perhaps even added a note about it in one of his diaries or scrapbooks, then we could claim with certainty:

All credit goes to Caminante!

Speculations and assumptions are inevitable components of any investigative work. I share my findings (and guesses) with you, the readers, and encourage you to choose your own most likely scenario from among the many possibilities presented in this text.

Notes and references

Fine Print:

© 2024 by H. Galic

No part of this online document, may be reproduced without written permission of the author.