If you ever find yourself wandering through a small cemetery in Yosemite Valley, you may recognize a few names on wooden markers or inscribed granite headstones. Indeed, in these graves rest some of the people closely connected with the history, growth and development of Yosemite, such as Galen Clark, J. M. Hutchings, J. C. Lamon, the photographer Fiske, George Anderson — the first to scale Half Dome — and others. Some names are less well known. These could be the graves of visitors or workers in the Valley, or perhaps family members of local residents. On the north side of the cemetery you will also find a dozen graves of members of the Piute and Yosemite Indian tribes.

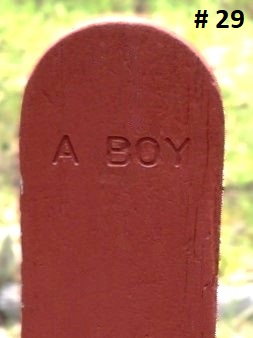

In this work we will focus on one grave that is now simply marked A Boy. When you enter the cemetery, it is the closest of the four neatly aligned graves in front of you, and slightly to the right (see pictures). This grave is also known as "Grave 29".

Although the cemetery at its current location was probably established in the 1870s, few travelers to the Valley were aware of it, and even fewer visited the cemetery in the next fifty years. Around 1907, incense cedar trees were planted to better delineate the cemetery, and around 1918, a fence was placed, enclosing about 39 graves identified up to that time. The first to systematically list the locations of known graves and names on grave markers seems to have been Mrs. Rose Taylor (a.k.a. Mrs. H. J. Taylor) in a newspaper article published in 1931 {1}. After describing all the known grave sites in the cemetery, she concluded her article with a paragraph about four other graves that she had heard about from Valley pioneers but could not find. She was told that "a man named 'Boston', another named 'Woolcock', a 'Frenchman', and a 'Boy' were buried somewhere in the southeast part of the cemetery". She was pretty sure that 'Boston' was the man who served as a toll-keeper for the Coulterville road, and who was murdered in 1875, but she had no clues about the other three sites.

Five years later, when she included a chapter on "Cemetery in Yosemite Valley" in her 1936 book, Yosemite Indians and Other Sketches {2}, she was able to say a bit more about location of those four graves. In the book, she described them as situated "south of the Indian burial lot [and] not clearly outlined". Although she said the graves had not been "in any way identified", she did echo what she had heard from Yosemite oldtimers several years before, again linking those graves to 'Boston', 'Woolcock', 'Frenchman', and 'A Boy'. She also wrote that "according to the pioneers, the first interment in Yosemite Cemetery was that of a boy drowned at Happy Isles", but she was careful not to connect that drowning directly with A Boy's grave or with any other grave in the cemetery.

In 1959, Brubaker, Degnan and Jackson's Guide to the Pioneer Cemetery was published {3}. The brochure proved very popular with Yosemite tourists. It contained a detailed map of the cemetery and its grave sites. Each grave — in a somewhat random manner — was assigned a unique number from 1 to 45. The descriptions of the graves in the text were then ordered by these numbers. A Boy's grave was numbered "29". In the text of the description, the authors now seem to have definitively connected grave "29" with the story of the boy who drowned near Happy Isles in the summer of 1870. It was also implicitly suggested that this grave was the earliest one in the cemetery. Here is their description:

(San Francisco Chronicle, Sunday, June 19, 1870, p.4):

Sad Termination

of an Intended Pleasure Trip to Yosemite Valley.

(From the Brooklyn Independent, June 18th.)

About two weeks ago, a party of six boys and two teachers from McClure's Oakland Academy left on horseback for the Yosemite Valley, among whom was Frank Tubbs, son of H. Tubbs, of this town; a son of Judge Campbell, of Oakland ; a son of Mr. Bonnestel, and a son of R. H. Bennett, the well-known grain dealer, of San Francisco, a boy about fifteen years of age. The party had been up to the Nevada Falls, and were returning when they reached the ford of the Merced river. One of the teachers took the lead and crossed first, the boys following after, one teacher coming last. Young Bennett was the last of the boys to cross. He rode a mule at the time, which became somewhat unmanageable. As the stream carried them down, the mule sunk into a deep place in the river, and young Bennett was thrown. The rapid tide took both under some logs that obstructed the stream at this point ; they soon appeared, however, at an opening, when the mule swam ashore. Young Bennett, who was a good swimmer, appeared to be struggling in the water ; he was, however, drawn under a second tier of logs, and the distance under water being so great before another clearing occurred, young Bennett was drowned. After a diligent search of two hours, his companions found his dead body a considerable distance down the stream. Yesterday morning his father received a letter from him, giving an account of the trip, and speaking of the enjoyment all the members of the party experienced during their sojourn in the valley. Shortly after reading this letter, he received a dispatch stating his son had been drowned, as described above. The father, of course, is almost heart-broken at this sad termination of what promised to be a most enjoyable experience in his son's life. Mrs. Bennett is on a visit at the East. Mr. Kerr, one of the teachers, brought the body of young Bennett back to the city of Oakland. For a distance of forty miles he was obliged to pack him on the mule's back. He arrived on Thursday [16th June] night.

[Note: Brooklyn Independent was printed in Brooklyn, Alameda County, now part of Oakland, not in New York City's borough with the same name (Brooklyn).]

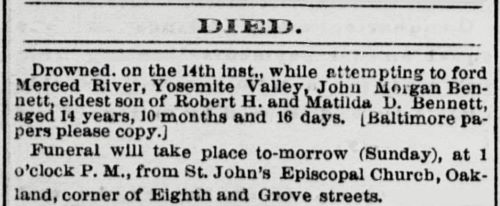

It is hoped that those few newspaper clipps are convincing enough to assure the reader that young John Bennett has never been buried in Yosemite Cemetery. In fact, his remains are laid to rest in the Bennett family plot, on a commanding piece of ground near the center of the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland. In 1871, a tall monument of California marble has been erected on the plot, with the following inscription: "In memory of John Morgan Bennett, eldest son of R. H. and Matilda D. Bennett, drowned in the Merced River, Yosemite Valley, on the 14th June, 1870, aged 14 years, 10 months and 19 days, a native of San Francisco, California." You can check the pictures of the monument at a free genealogy website.

The rest of this article describes the research that eventually revealed the identity of A Boy. The process of discovery was not based on finding a previously unseen memoir from some old-timer, written many years after their childhood in Yosemite. To the contrary, the most important clues to solving this puzzle from the 1870s were found in a short contemporaneous text by a now-forgotten 19th-century author, known among her admirers as the "Poetess of Yosemite".

Mrs. Washburn

Jean Lindsay Bruce (~1834-1904), future Mrs. Washburn, had her poems published in the East Coast newspapers at the early age of 14. She became a regular contributor in the Sunday Dispatch, New York, in September 1850, shortly before her 16th birthday. In December 1856, the following notice was published in the New York Daily Herald: "Testimonial to American Genius. — Our popular young poetess, Miss Jean L. Bruce, of Williamsburg, N.Y., has been the recipient of a magnificent watch... as a reward for one of her poetical productions. This young lady is one of our gifted ones, and is distinguished for great natural talents as well as varied accomplishments..."

In late May 1861, accompanied by her brother John, Jean reached California via Panama, and joined several other members of her family who were already well established in Mariposa County. She became a regular contributor to the Mariposa Gazette two months later. Editors liked her literary works, and it didn't take long for her to began publishing her poems and stories in a dozen California daily and weekly newspapers. In 1865 she married one of her brothers' business partners, Albert Henry Washburn, at Mariposa, and the couple then moved to Merced. She continued writing, now under the name Mrs. Jean Bruce Washburn. After each of her frequent visits to Yosemite, she would express in verses her delight and exhilaration with the beauties of the Valley surrounded by waterfalls and cliffs. In 1871, the A[nton] Roman Publishing Company of San Francisco presented a 16-pages booklet with some of her Yosemite rhymes, and from that time the "Poetess of Yosemite" became even more popular. However, Yosemite was not the only stimulant for her creativity. In fact, any event that stirred her feelings was a good theme for her poetical inspiration. Ultimately, it was this inner drive of Mrs. Washburn's that helped us to gain important clues about the young person buried in grave 29.

After a long and snowy winter of 1875/76, the editor of the San Joaquin Valley Argus, Robert J. Steele, announced in the "Personals" section of his Merced newspaper that Mrs. Jean Bruce Washburn left Merced for Yosemite on May 28, 1876. Being clearly an admirer of Mrs. Washburn's poetry, he didn't miss the oportunity to compliment her by adding that "Merced should be proud of this gifted poetess, a lady of rare literary ability, queenly in her carriage and address, of high and noble mind, yet unpretentious as a little child in her everyday life." It sounded a little over the top for a simple vacation notice, but she was happy to see it. In return, she showed her gratitude by sending the editor a detailed description of current news from the Valley as well as a selection of interesting events that had occurred since her previous visit to Yosemite in the late summer of 1875.

One of the items on her agenda for this trip was to check on the progress of work on the granite monument at the grave of her Yosemite friend James C. Lamon. Mr. and Mrs. Washburn probably contributed financially to that project. When she was returning from Lamon's grave site, she must have happened to notice another grave in another part of the cemetery. One of the companions then told her that it was the grave of a boy who was accidentally shot here in the Valley by a bullet from his comrade's pistol. Severely wounded, and after long suffering, despite his mother's tireless care and prayers, the boy died several weeks later. This story must have resonanted strongly with Mrs. Washburn, who lost her own son a decade earlier. That evening she sketched a few verses dedicated to that boy and his mother, then on May 30, 1876, sent the stanza along with the rest of her report to the editor of the Merced's newspaper. Here is the excerpt from her letter describing her visit to Lamon's memorial at Yosemite Cemetery {4}:

[... Mr. Lamon's] monument, now being built at a cost of about $7,000 by loving friends and relatives, gleams white in sight of Yo Semite's first schoolhouse. [Schoolchildren] who knew his kindness gather wild cherries near his grave. A noble boy who perished by the shot accidentally fired by a comrade, and who endured his long suffering without a murmur, lies buried near.

Not all the power of a mother's tear

Could save that boy from his mountain bier,

Yo Semite's artillery shall roar

A sad requiem forevermore.

Farewell, kind friend! this vale shall see

What it has lost in losing thee.

[...]

There wasn't much information in the article about the time frame or the names of the people involved, but still enough to begin a broad general newspaper search of accidents reported from Yosemite Valley prior to May 30, 1876, the date Mrs. Washburn sent her letter. Then, step by step, the full extent of the events slowly unfolded.

Year 1874: Twenty Days in July

The key episodes of our story occurred in July 1874, but this was preceded by a few brief notices in Oakland and San Francisco newspapers in late June. The papers reported that a group of young men from Oakland had taken a trip to Yosemite Valley and the Big Trees. Readers will later learn the names and ages of these young excursionists: Thomas Wells (about 19) and—possibly—his brother William Wells (about 18), Frank Phipps and William Swinton Jr (both about 20), Henry Jenkins (about 23) and the youngest, William Wyatt (about 17). At first, everything went well, and reportedly "the lads were having a delightful jaunt". Then on Sunday, July 5, 1874, a shocking accident occurred in Yosemite, and the lives of several participants and their families were suddenly shattered into pieces. We will try to understand what actually happened by reviewing relevant articles from contemporary newspapers.

The earliest reports of the disturbing incident in Yosemite appeared in newspapers on Wednesday, July 8, three days after the event took place:

(Oakland Daily Transcript, Wednesday, July 8, 1874):

A Sad Affair.

A short time since a party of gentlemen

left this city to go on a pleasure trip to Yosemite. Intelligence has just been made

public that while in the valley one of the

number in carelessly handling a revolver,

shot his comrade in the back. A messenger

was sent to Chinese Camp for a physician, and

at last accounts he [the victim] was alive, and hopes entertained of his recovery, which we trust will

prove true. The young men are well known

here, and in consideration of that fact we

withheld their names from publicity. The

mother of the young man, from whose hands

the shot was fired, went to the scene yesterday afternoon. The parents of the other

started there on receiving a telegram.

————————————

(San Francisco Bulletin, Wednesday, July 8, 1874):

Shocking Accident at Yosemite. — Among a party

of boys residing in Oakland who left for Yosemite

Valley afoot, a few weeks since, was Willie Wyatt, a

bright little fellow of seventeen years. The letters

from the lads were satisfactory in every respect

and until yesterday it was supposed they

were having a delightful jaunt. Some time

during the afternoon of yesterday a dispatch

was received at Oakland announcing that young

Wyatt had received a severe wound through the accidental discharge of a gun in the hands of one of his

companions. Another dispatch, received this morning from one of the party, says that a physician who

was summoned to attend Wyatt has pronounced his

recovery impossible.

More details, sometimes contradictory, became available in the days that followed:

(Oakland Daily Transcript, Thursday, July 9, 1874, p.1, col.2, top):

Accident at Yosemite.

In yesterday's issue we alluded to the fact

of an accident in Yosemite valley, happening

among a party of young men who left this

city a few weeks ago on a pleasure trip. The

youth who was shot is named William

Wyatt, and has parents living here. He attended the State University, and is highly

esteemed by those who know him. A companion named Henry Jenkins, was handling

a revolver, when it accidentally went off, the

contents going into the back of his friend

and comrade. The latter is a son of Hon.

T. F. Jenkins, who lives on Twentieth street.

From all accounts of the sad accident no

blame is attached to Mr. Jenkins, as it was

purely accidental. A telegram was received

yesterday to the effect that young Wyatt

could not possibly recover.

Note: William Wyatt wasn't actually a student at State University yet. He was probably admitted and would have started his freshman year at Berkeley in late August if he hadn't lost his life.

————————————

(Oakland Daily News, Friday, July 10, 1874):

It is stated that the recovery of Wille Wyatt, who was accidentally shot by a companion in Yosemite Valley, last Tuesday, is impossible.

————————————

(Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, Friday, July 10, 1874), p.3 col.2, middle):

Not Necessarily Fatal.

A dispatch received in Oakland last night from Mrs. Wyatt, mother of the boy who was shot in Yosemite valley, states that the physicians are hopeful of his recovery. The accident occurred on the 5th inst., and was not the result of carelessness on the part of young Jenkins. The latter was in the act of placing his revolver in its scabbard, when for some unaccountable reason the weapon was discharged, the ball taking effect in Wyatt's back, between the shoulders and ranging upward. He was standing about twenty feet from Jenkins at the time.

————————————

(Tuolumne Independent, Sonora, Saturday, July 11, 1874, p.3, col.5, bottom):

Sad Accident at Yo Semite.

Via Chinese Camp we learn that Willie Wyatt, of Oakland, a young man of 17, one of a small party of boys who started on a pedestrian excursion to the Yo Semite a few weeks ago, was accidentally shot in the valley on Sunday last. At the time of the accident the young man was saddling his horse. A companion in camp was loading a navy six-shooter, which was accidentally discharged, taking effect in the back, literally breaking it. His condition is critical in the extreme, and in all probability he cannot recover, as the lower portion of his body is paralized. The parties are residents of Oakland. Dr. Lampson of Chinese [Camp] is attending him and every attention is being bestowed on him by the residents of the valley.

Note: At that time, there was no year-round resident doctor in the Valley. One of the foothill doctors who was willing to travel all the way to Yosemite was Royal M. Lampson. He practiced medicine in Chinese Camp from 1870 until his death in 1885.

————————————

(San Joaquin Valley Argus, Merced, Saturday, July 11, 1874, p.2 col.3, bottom):

A Sad Affray.

[...]

We suppose this is the same affair which caused Dr. Lee of this place [Merced?] to be telegraphed for on Sunday or Monday last. The telegram was from a man named O'Bryan [John C. O'Brien], and we are informed that he was called to attend a young man Wyatt, a Yosemite tourist who had been shot by a comrade. Up to this time we have heard no further particulars. The Doctor went post haste, having engaged Washburn & McCready to put him through in a night, buggy team, for one hundred dollars the round trip. We have been anxiously expecting the Doctor back and fear that the case is a more serious one than is indicated by the information vouch-safed by the [Oakland] Transcript of July 8th.

Since above was in type we learn that the wound is pronounced fatal by physicians and that the shot was fired by T. H. Jenkins, son of T. F. Jenkins, Esq., formerly of Snelling.

On Saturday, July 11, one of the Oakland newspapers published a note to the editor from John O'Brien Wyatt, Willie's older brother, written the day before, on July 10. The brother appealed to readers not to blame Henry Jenkins for the accident. He also disputed reports that there was no hope for Willie's recovery. That prognosis "was based on the first examination of the wound", wrote John, "but since that, said report has been contradicted. At latest accounts, there was hope for recovery. This morning [July 10] I received a message that Willie was resting quietly, and that our mother had arrived to Yosemite."

In addition to John's note, the paper also published two letters from eyewitness Thomas A. Wells, who was a participant in the ill-fated excursion. Both of Thomas' letters were written in Yosemite on the day of the accident, July 5, and were provided to the editor by John Wyatt:

(Oakland Daily News, Saturday, July 11, 1874):

Yosemite, July 5, 1874

[From: Thomas A. Wells]

To: John Wyatt

My Dear Friend : Undoubtedly you will have heard what I am about to tell you ere this shall have reached you. It is my sad duty to inform you of the terrible accident that has befallen your brother Willie. He was accidentally shot this morning [July 5] about eleven or twelve o'clock. The wound (to speak plainly) is extremely dangerous. The way in which it happened is this: Henry Jenkins and myself had been out hunting the horses. Henry found them first, and to let me know he fired off his pistol. When we reached camp he went off one side and commenced loading while the rest of us saddled our horses. He had finished loading, and was in the act of returning the pistol to its scabbard when it went off. Your brother was standing some fifteen or twenty paces off, saddling his horse; he had his back toward Henry, and the ball entered between the shoulders, ranging upward and to the left. John, I have always been plain and straightforward with you, and forgive me if I am now, but the wound is exceedingly dangerous and is likely to prove fatal. And John, I have a request to make of you, and all of your family. It is this: Whatever the consequences are, do not blame Henry Jenkins for it. He is almost crazy, and believe me when I say that the accident was not in the slightest degree the result of carelessness. The caps we have been using have become damaged and go off very easily ; this one went off simply by the pressure of the hammer after it had been down some seconds. I got a wagon as speedily as possible and had him taken to Hutching's, where he shall have every care and attention. At the present time of writing he is sleeping quietly and the indications are favorable. I have telegraphed to Chinese Camp for a doctor, and also to [Mr.] J. C. O'Brien to come immediately. I will write you very often, and in the meanwhile let us hope for the best.

Your Friend,

Thomas A. Wells.

Note: John C. O'Brien was Willie's uncle (Mrs. Wyatt's brother), and long time business partner of the late Mr. Wyatt.

Yosemite, July 5, 1874

[From: Thomas A. Wells]

[To: Mrs. Wells]

(Extract):

Henry [Jenkins] is almost frantic. I don't know what to do with him, he is not in the least to blame for carelessness for he went clear out of camp to load, and at no time during loading was the pistol turned toward any of us, only when putting it away...

Death and Burial at Yosemite.

After a brief lull, the Willie Wyatt case was back in the headlines:

(Oakland Daily Transcript, Sunday, July 26, 1874, p.3, col.1, bottom):

We were informed yesterday that young

Wyatt, who was shot in Yosemite accidently

a few weeks ago, is dying. That ever faithful friend [of?] his father is attending to his every

want and necessity, and his friend, the innocent cause of the shooting, cannot be

prevailed upon to leave his comrade's bedside.

A short time ago, it was thought that Master

Wyatt would recover, but symptoms have

now set in dispelling all hopes of recovery.

The young man is well known in this community, and a large circle of friends will be

pained to hear this news. He was a young

man of brilliant promise, ripe intellect for

one so young, generally esteemed and respected.

This information quickly spread to a dozen other newspapers. Then, on August 1, Willie's death was confirmed by his family:

(Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, Saturday, August 1, 1874, p.3, col.2, middle):

Death of Young Wyatt.

A brother of Willie Wyatt, of Oakland, who was accidentally shot by his companion, Henry Jenkins, on the 5th of July last, called in this afternoon and showed us a dispatch stating that the unfortunate boy was buried on the 29th [Wednesday, July 29, 1874]. The dispatch does not state the time of his death, but it was, probably, the day previous to his burial [Tuesday, July 28, 1874]. His mother sent the sorrowful news. Young Wyatt was a student in the State University, and a fine, promising youth every way. Jenkins, his companion, is from Oakland.

————————————

(Oakland Daily News, Tuesday, August 4, 1874):

Willie Wyatt, who was accidently shot at Yosemite on the 5th of July, died on the 28th and was buried on the 29th in the valley.

The burial in the Valley was also confirmed by the

Daily Alta California,

The Tuolumne Independent, (Sonora),

The Union Democrat, (Sonora),

and other newspapers.

There is no doubt that the presented newspaper reports, combined with Jean Washburn's description and verses, prove with absolute certainty that it is William "Willie" Wyatt (~1857 - 28 July 1874), who is buried in grave #29 at Yosemite Cemetery. A Boy now at long last has a name.

Epilogue: End of the line for the Wyatts

I really struggled trying to understand why the family stopped maintaining Willie's grave in the Valley. What was once probably a wooden cross bearing his name on a humble grave, they allowed to decompose, to be lost and to disappear not only from the burial site but also from memory. It took a bit more research to come up with some sort of explanation.

Willie Wyatt's parents, William (Sr) and Margaret E. Wyatt (nee O'Brien), had at least six children. However, by 1863, the year of Willie's father's death, only four were listed in the Probate Court records. When Willie lost his life in 1874, three siblings remained alive. At that time, John O'Brien Wyatt was about 21 years old, Maria E. Wyatt about 18, and Henry Clay Wyatt, about 14 years old. None of them attended Willie's funeral in Yosemite. It is believed that only Willie's mother Margaret (then aged about 39) and Margaret's older brother John C. O'Brien (aged 52) were present, and they alone knew, or thought they knew, the exact location of the grave and how to find it in a vaguely outlined and unkemped cemetery. Note that in the summer of 1874, perhaps only one other burial place in the cemetery was in use. Even that grave was probably only provisionally marked {5}. Willie's mother Margaret may have planned to visit his grave on the first anniversary of his death, in July 1875, but another major event in her life probably changed her plans. In May of that year she married again and became Mrs. J. M. Thompson. Similarly, Willie's older brother John had just graduated from the State University in June 1875, and the intense search for his next employment likely prevented him from making the trip to Yosemite. I don't know if there were any visitors to the grave site in the next few years, but after Margaret's and her brother's deaths (both died in 1885), all visits most likely ceased. It would be nearly impossible for Willie's siblings to discover where he was buried unless they had escorted their mother to Yosemite at least once in the past.

One common thread connects the lives of Willie's siblings in their later years: they left no offsprings. Willie's sister Maria married Mr. James S. Taylor in 1877, but he died a few years later. They had no children. Maria died probably at the turn of the century. Her brother John never married, and died in 1920. Youngest brother Henry died in 1921. Judging by his last will, he left no children either. With Henry's death, the last member of A Boy's immediate family disappeared, and neither the family name nor their genetic material was passed down to another generation {6}.

And what happened to the other tragic character in this drama, Henry Timothy Jenkins, whose pistol malfunctioned? He probably carried the burden of his young friend's death for years, perhaps even to his dying day. After the 1874 accident, Henry remained in Oakland until about 1881, working at various jobs. In some records his occupation is described as "agent", then "house mover". It seemed as if he tried to avoid all publicity at all costs during the remainder of his life. Practically, almost nothing could be found about him in the public media. A few sparse lines in Oakland directories and voter lists in California and Arizona provide only a very rudimentary picture. From 1882 to about 1884, perhaps encouraged by his brother-in-law, who was a mining engineer, Henry Jenkins worked in Tombstone during the silver mining boom days in that part of Arizona. In 1886 he may have stayed briefly in Merced, but by 1888 he was back in Oakland (occupation "miner"), living with his father, mother, and three brothers in a spacious house at 1362 Eight street. In May 1892 he was registered as a voter (occupation "miner") in Bear Valley, Mariposa County. A few years later, in August 1896, at the age of 45, he moved to Madison precinct in Fresno County, still registered as a "miner". The last public mention of Henry appears to be in the 1898 Fresno County register of voters, but we don't know if he actually voted that year, or if he may have moved elsewhere or even died. It is certain that he was no longer alive in July 1900, but we don't know when exactly and where he was buried. Henry was survived by his mother, two married sisters and two younger brothers {7}.

As noted above, Yosemite's librarian, Mrs. Taylor, (who was not related to Maria Wyatt's husband, James Taylor), spent some time exploring Yosemite Cemetery in 1931, and then wrote a lenghty newspaper article about her visit. She learned from some old-timers about a group of very old and almost unrecognizable grave sites. Although she was instructed to focus her search to the southeast corner of the cemetery, she was unable to find any sign of those graves at the time. However, in the years since, four early graves have been rediscovered, including one referred to as the "boy's grave", first to Mrs. Washburn in 1876, and later to Mrs. Taylor in 1931. In more recent times the four graves have been nicely restored by the National Park Service (NPS), but the boy remained nameless. Wouldn't it be wonderful if the NPS could now take another step, and put Willie's name on the marker?

Here Lies William Wyatt (~1857-1874)

"A Boy"

Notes and references

{1} Stockton Daily Evening Record, Saturday, February 14, 1931, p.26

{2} Yosemite Indians and Other Sketches, by Mrs. H. J. Taylor. Published by Johnck & Seeger, San Francisco, 1936. Free access to the entire book is available at HathiTrust, or at Dan Anderson's Yosemite Online website. Alternatively, follow the link directly to Chapter 9, Cemetery in Yosemite Valley.

{3} Guide to the Pioneer Cemetery, (Yosemite National Park), by Lloyd W. Brubaker, Laurence V. Degnan and Richard R. Jackson. Published by the Yosemite Natural History Association in cooperation with the National Park Service, 1959. This booklet was printed as a "special issue" of the periodical Yosemite Nature Notes, Vol.38, No.5, May 1959, pp.58-74. A slightly revised and updated version was published in 1972 as a separate, 13-pages brochure. Title and authors remained unchanged. More recently, the guide was completely revised and published as Guide to the Yosemite Cemetery, by Hank Johnston and Martha Lee. Published by the Yosemite Association, 1997, 32-pages. For free access to the 1972 version use Dan Anderson's Yosemite Online website.

{4} San Joaquin Valley Argus, Merced, Saturday, June 10, 1876, p.4, col.2, top.

[Read this article]

{5} Here I allude to grave 31, marked Woolcock. This may have been the Mr. Woolcock who "broke his neck" while working on the Coulterville-Yosemite wagon road on June 22, 1874. The Mariposa Gazette (and Brubaker et al. {3}), called him "Woolcott". The Union Democrat, Sonora, says a body was found in Cascade Creek on June 24, and identifies the drowned man as "Wilcox". However, the usually reliable 1872 edition of Great Register of Mariposa voters confirms his name as Henry Woolcock, age 58 (in 1872), born in England and naturalized in 1865. So we know that he died about a month before Willie Wyatt. We also now know that Willie was buried on July 29, but there is no record of when exactly Henry Woolcock was interred. For example, he may have been temporarily buried near Cascade Creek, and his remains only later reburied in Yosemite Cemetery.

{6} One of John O'B Wyatt's obituaries mentions several of his California cousins who survived him: Hugh J. Corcoran (of Auburn), and siblings James Mitchell (of the Central Valley) and Katie Mitchell, married to William West (of Oakland). It might be interesting to do some genealogical research to determine how closely these three were related to the Wyatts and if any of their descendants are still alive.

{7} Four siblings survived him: Annie Elizabeth Jenkins (a.k.a. Mrs. Samuel A. Widney), who died in 1942; Edwin Jenkins, still alive in 1919; Harriett Mary Jenkins (a.k.a. Mrs. James McCaw), who died in 1937 (she had at least four children); and Horatio Freeman Jenkins, who was still alive during the 1930 Federal Census window.

Fine Print:

© 2024 by H. Galic

No part of this online document, may be reproduced without written permission of the author.